Over the last few blogs, we’ve discussed how badges are one of the most common forms of gamification used in eLearning and why they can be useful. Today, let’s examine another very popular use of gamification: leaderboards. Leaderboards implemented into a learning environment typically involve displaying the rankings of students according to some quantifiable metric, such as performance (grades). Leaderboards are a popular tool because they are relatively easy to install (Hamari et al., 2014) and because they ideally encourage student achievement and engagement through engendering competition (Cigdem et al., 2024).

There is significant evidence to suggest that leaderboards can positively affect both students’ course engagement (Barata et al., 2017 and Scales et al., 2016) and performance (Christy and Fox, 2014; Landers et al., 2017, 2019; Bai et al.,2021). Equally, however, Bai et al. (2021) assert “other studies show no, mixed, or negative effects” (Mekler et al., 2017; Mollick and Rothbard, 2014; Zuckerman and Gal-Oz, 2014). The point here is to illustrate that rigorous study has been conducted on the efficacy of leaderboards in learning, yet academia appears unable to fully reconcile mixed findings.

This blog will be split into two parts. Here, we will discuss plausible causes of these discrepancies, such as leaderboard types, user/course characteristics and context, and scale. In the second part, we will take a step back from academia to focus on how video game leaderboards have evolved to see if gamification can gleam some useful insight from its origins.

How Leaderboards Differ

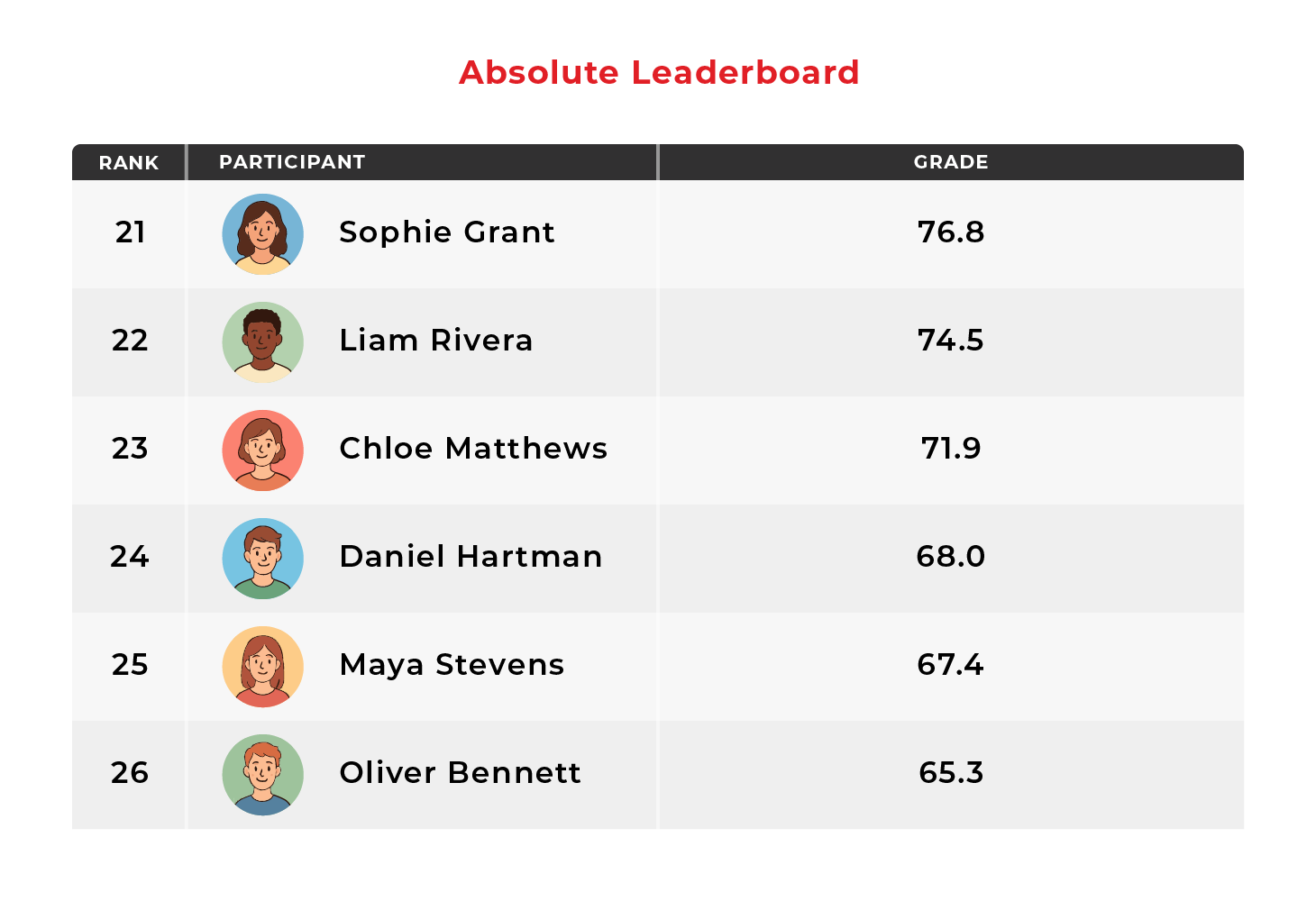

One of the most likely reasons leaderboards vary in effectiveness for learning is that leaderboards themselves come in many shapes and sizes and range in how they are utilised. In one example, Bai et al. (2021) studied how “absolute” and “relative” leaderboards might affect students’ course engagement differently. Absolute leaderboards display the literal ranking of each individual in a course, whereas relative leaderboards only show individuals relative to their nearby peers (for example, those with similar grades). These are not strictly binary or mutually exclusive; leaderboards come in a variety of forms, and these categories serve as just one useful method of classifying common iterations.

Notably, relative leaderboards do not display overall rankings. The purpose of this is to remove disincentives that competitive environments can create for weaker students. Low-ranked participants perceive a great distance to top rankers, which can result in demotivation (Ninaus et al., 2020). Therefore, they hypothesised that top and bottom performing students would respond differently to these different leaderboard designs. The results were mostly unsurprising: relative leaderboards resulted in less competitiveness than absolute leaderboards, leading to lower overall course engagement but with bottom-ranking students feeling more encouraged.

The study also provides insights directly from the students themselves. Students of all ranks appeared to benefit from leaderboard implementation. Middle- and bottom-ranked students displayed an overall positive sentiment towards leaderboards. Top-ranked students tended to reap the greatest motivational rewards due to proclivity for competitiveness – “I made more effort to climb to make sure I was at the top, after knowing my position.”

However, a common theme among lower-ranked participants was saving face, seemingly concerned about reputational loss potentially resulting in discouragement: “I prefer anonymous ranking, so that we can feel free from peer pressure and focus on our own improvement.” Leaderboards can differ depending on whether rankings are public or anonymous. Relative leaderboards convey some degree of anonymity by design, since actual placements are hidden and users can only see similarly-ranked peers. This is likely part of the reason lower-ranked students feel more encouraged when relative leaderboards are implemented rather than absolute leaderboards.

Of course, designers can modulate the degree of anonymity no matter which type of leaderboard they employ. For example, Bai et al. (2021) propose an absolute leaderboard design where only top ranks are fully public; otherwise, users are only able to view their own rank. Consequently, top-ranked students retain that sharp competitiveness resulting in greater performance and engagement, while bottom-ranked students avoid the stress of reputational loss and improve at their own pace, benefitting from leaderboards in other ways such as inclination to cooperate with other students of similar rank.

How Context Differs

Through these examples, it is clear leaderboards can vary greatly in design, resulting in diverse student experiences. However, it is equally important to recognise that these experiences are also determined by differences in context. As an example, consider the insight of another middle-ranked participant from the above study: “I prefer the public [absolute] leaderboard. As adult learners, we should be psychologically prepared to acknowledge the distance from high-performing classmates.” Their opinion contrasting directly with the common sentiment on reputational preservation, this student introduces a salient concept: classroom demographic and individual personality noticeably impact how leaderboards affect users.

A myriad of other characteristics can impact the effect of leaderboards on individuals – personality, life experience, proclivity for resilience or competitiveness; the list is interminable. Environmental context is also important. Different faculties or userbases are likely to respond to leaderboards in unique ways due to their specific conditions. Even culture has a noticeable impact. For example, in the Bai et al. (2021) study, they specifically assert the student cohort is from an Eastern background, implying cultural upbringing can skew student perspectives or receptiveness based on norms and customs.

Finally, students consistently stated that they compared themselves more with their own groups rather than relative strangers in the class: “I only compared with the upper ones in my group. I was also curious about the positions of others from different groups, but I didn’t make comparisons with them.” This implies that reputational losses are contextual as well; individuals seem more concerned with saving face or performing well in front of people they know more directly.

Interserv’s Cove Leaderboards – How Scale Matters

Ultimately, designers not only have to consider what type of leaderboard to employ, but also acknowledge the unique conditions of their users. How might instructional designers judge when leaderboards are appropriate, and decide how to incorporate them? Let’s now look at an Interserv example for one potential answer to this question.

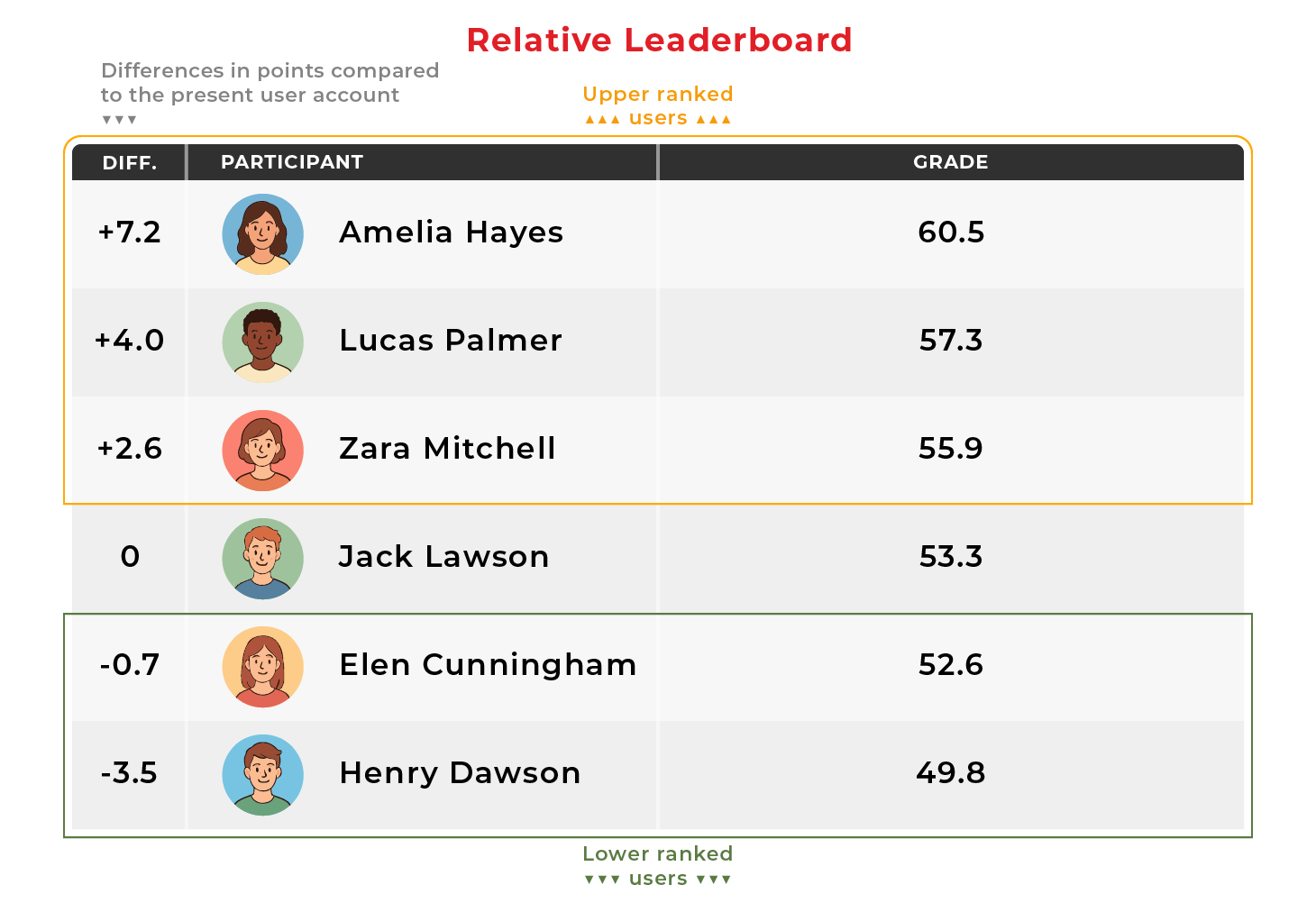

The Cove is the Australian Army’s professional development platform. Interserv has gamified the service using leaderboards. These leaderboards avoid the usual pitfalls that plague lower-ranked user motivation in two primary ways while conferring all the typical benefits. Firstly, the leaderboards focus on engagement rather than performance. “XP” (Experience Points) determining your position on the leaderboards is accumulated through participatory actions, such as reading articles, or commenting on forum posts. Hence, XP is accrued through engagement. This is important because studies show lower-ranked users feel simultaneously less insecure and more encouraged when the metric involves participation rather than performance, as referenced in our Digital Badges blog.

Secondly, the scale of these leaderboards is much larger than the average classroom learning environment. A typical classroom might have thirty students; a faculty cohort, a few hundred. The Cove, in contrast, has thousands of users. As scale increases, reputational concerns diminish drastically. The excerpts from students in the previous study clearly indicate that students care more about saving face when compared directly with people they know. A student might know everybody in their classroom; a Cove user, however, is far less likely to be recognised by their peers amongst thousands of others. This is further exacerbated by the nature of usernames. These can carry inherent anonymising potential, since users can choose usernames unconnected from their real identities. Consequently, Cove users are less likely to feel concerned about reputational damage.

What’s Next?

Although leaderboards often encourage performance and engagement, they should only be implemented for the welfare of users and curated for their specific needs and context. For example, The Cove’s leaderboards act as encouragement for Army personnel to utilise the platform in a way that benefits them, since XP is earned through engaging with content directly relevant to progressing their careers.

In the second part of this blog, we will explore how leaderboards have evolved in the gaming sphere. These evolutions include elements like more nuanced ranking systems, hybrids of absolute and relative leaderboards, and supplementary gamification tools such as cosmetic rewards for achieving certain ranks. Through examining these, designers could apply some of the techniques employed by video game developers to further enhance leaderboard efficacy in learning environments.